Headphones and other headaches

The question often comes up about what microphones or earphones were used with what aircraft radios, and I've come

to the conclusion that this is a question that cannot be answered with any certainty - at least as it is posed.

The reason for this ambivalence is that microphone or earphone usage was rarely coupled with a particular radio,

and in fact was far more associated with the branch of Service and particular aircraft involved, and even more

specifically, the type of interphone system

installed in the plane. Even earphones or microphones occasionally mentioned in the various radio manuals may

or may not have been the ones predominantly used in actual practice.

Caveat: Like the microphone section, this page is not really about what likely formed a

significant chunk of headphone usage in

aircraft during the war. Many of those phones were designed to be installed in flight helmets, and while wearing

one in your hamshack of a summer night with a background of Wright radial engine recordings may seem sorta neat, it

is not comfortable for long periods, and it will draw quizzical looks from your neighbors or the occasional cat that

peers in your window. Nor is it concerned with the other class of earphones that today are called earbuds, which insert into

the ear and effectively shut out extraneous noise at the expense of comfort and cleaning. They saw far more use in ground and

Navy shipboard settings.

Instead, the headphones mentioned below are those traditional aircraft variations that are more useful to a radio amateur in

a relatively conventional setting.

The headphones used in WWII American aircraft are basically divided into two camps - Signal Corps and US Navy.

Unfortunately for the collector trying to make sense of the mess, it doesn't end there.

The Signal Corps versions provided to the AAC/AAF for "non-helmet" use in WWII aircraft were fairly

straightforward. First ya have your high impedance HS-23. Then ya have your low impedance HS-33. Well, shucks, that

seems to be pretty much the extent of it...heh. The primary difference between the two was impedance, but the

other markers were more subtle. The HS-23 had a (short) black "bail-out" PL-54 plug

on the end. The HS-33 had a red PL-354 "bail-out" plug that detached more easily in any frantic "move it or die" situation.

The ubiquitous HB-7 headband seems to have become the USAAC standard back before the war,

and the shift from high impedance to low impedance headsets was simply a change from

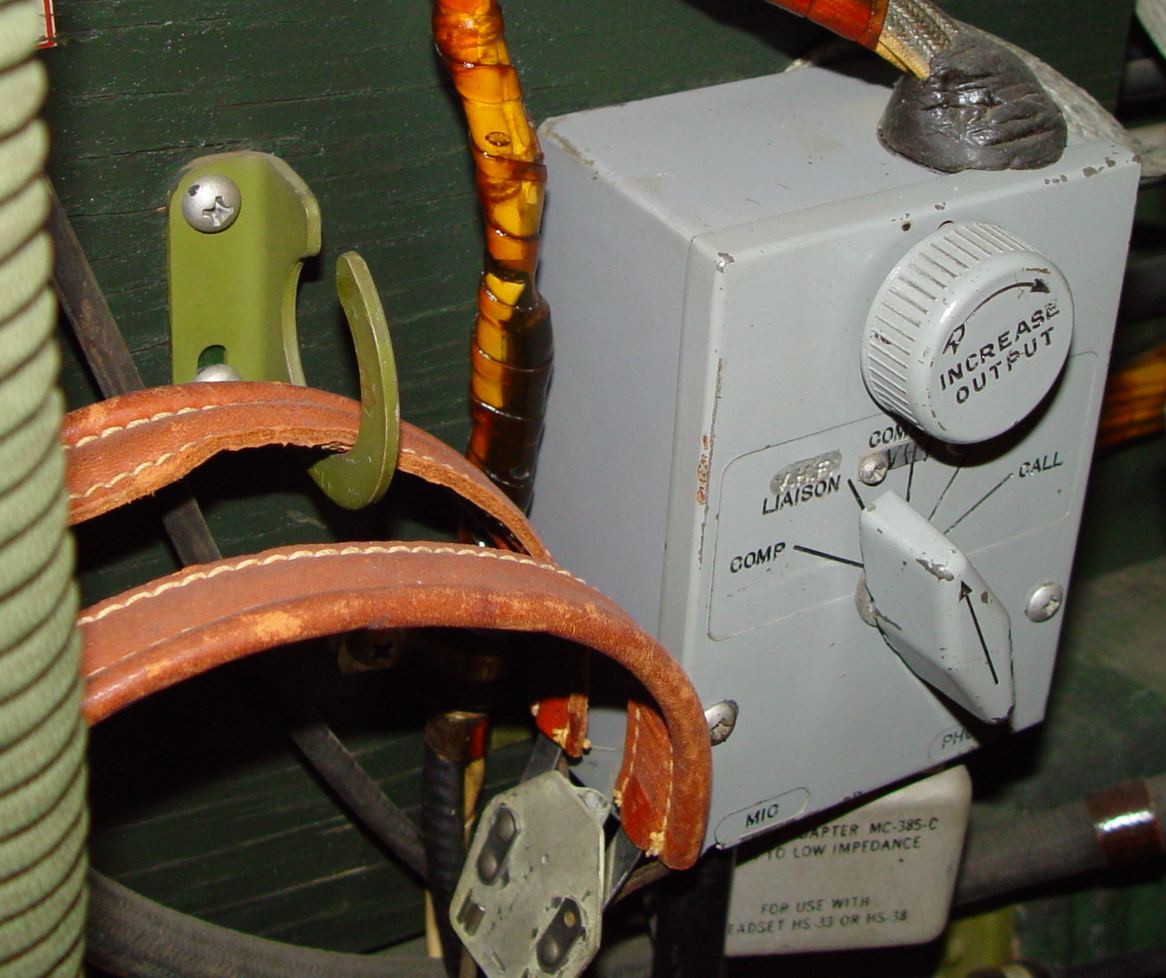

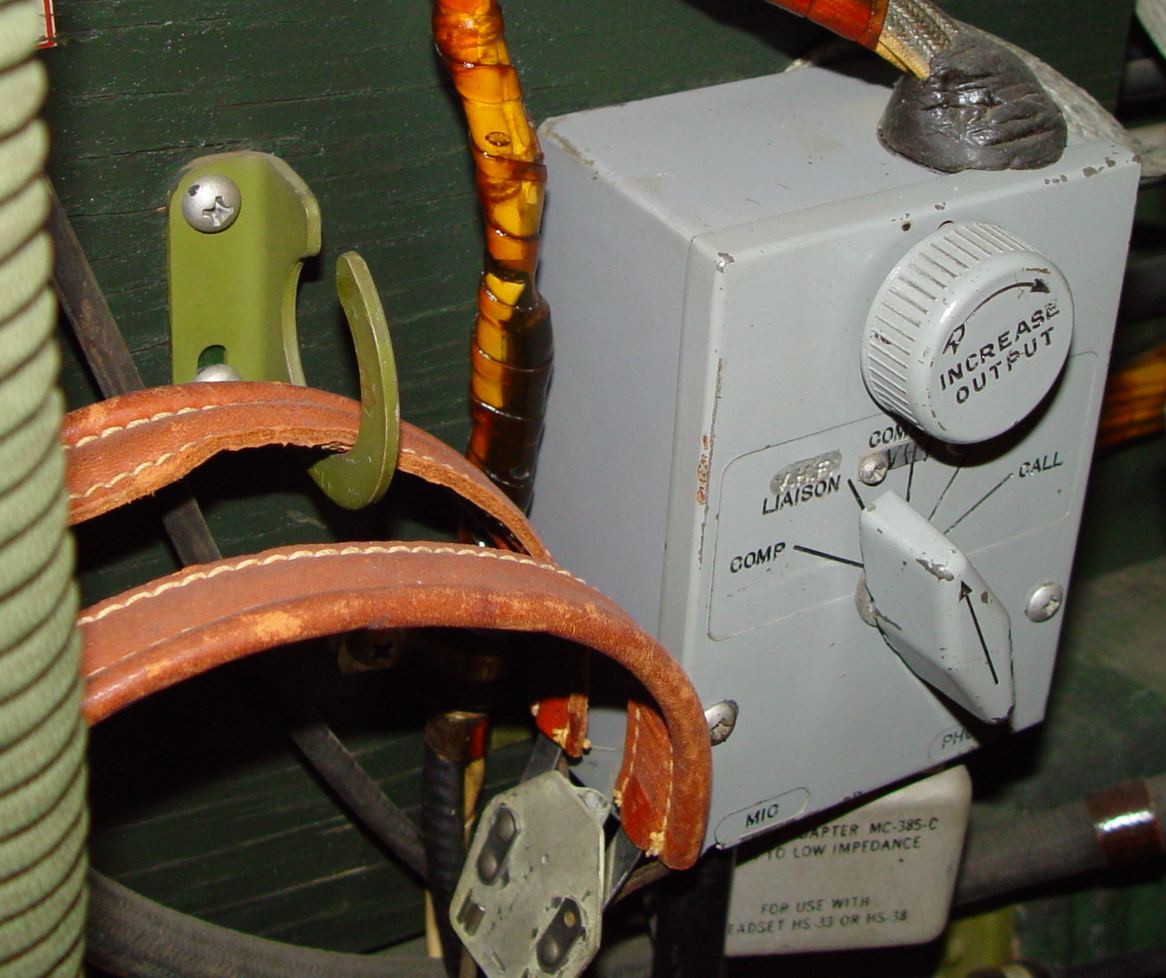

2,000 ohm R-14 to 300 ohm ANB-H-1 elements that clipped onto the headband. Unfortunately, so many high impedance headsets were already fielded that a plug-in

transformer impedance adapter was introduced to make the transition more palatable to the logistics chain, the

MC-385-* (seen in the bottom photo). Interestingly enough, the Navy evidently made the switch to low Z

headphones much earlier than the Signal Corps, apparently because low impedance headphones were more reliable

and less expensive to make. A Naval Research Laboratory training manual dated 1 August 1936 mentions the same

low Z headphones called out in an August 1945 directory listing, so any change had to occur earlier than that.

The ear cushion (more properly known as the socket) used in USAAF aircraft was a result of Bell Labs and Harvard Electro-Acoustic Laboratoris studies.

The Army version, labeled the MX-41/AR, was an all rubber design that mixed foam and hard rubber to totally

enclose the ear and at the same time provide a much higher degree of comfort, compared to the 1930s hard rubber designs. The Navy had a different approach with a

chamois covered cushion produced by the NAF (Naval Air Facility) system. The nomenclature was NAF-48490-1 and is still available through surplus outlets.

More comfortable in hot climates, the chamois absorbed persperation and became popular with both Navy and USAAF pilots.

As if to confound the situation, the Navy found reasons to make it a lot more complex. Navy aircraft headphones

were divided into four different "classes", as follows:

Class A (Right hand, short cord)

Class B (Left hand, short cord)

Class C (Right hand, long cord)

Class D (Split receiver headset)

All of these apparently had a generic Navy number 49015 for the leather flight helmet installation, but are

composed of a mélange of numbers for the piece-parts. Just to give you a flavor of the complexity, I've included

some excerpts of the mind-boggling entries from NAVSHIPS 900,109 at

NAVSHIPS mania.

The training manuals of the day describe the 49015 Navy headphones in this way:

"These receiver headsets are designed to operate with aircraft receivers having a low impedance output coupling

circuit. The spacing between the diaphragm and the pole pieces is such as to permit the receivers to operate at

any level up to a 50 miiliwatt level without the diaphragm touching the pole faces. The magnet cores used in

these headset are of 30% (minimum) cobalt steel. Each telephone unit has an impedance of 300 ohms at 1,000

cycles making an impedance of 600 ohms for the headset. The DC resistance of each of these units is only 60 ohms.

The primary resonant peak occurs within the limits of 1,000 and 1,200 cycles, and the overall frequency range

is 200 to 3,000 cycles. The telephone unit fits into mounting cups which fit leather helmets. A short cord is

attached to the telephone units terminating in a snap arrangement permitting easy removal." Somewhat tongue in

cheek, exactly why it was important to a logistician or technician to be aware that the pole pieces were made of

30% (minimum) cobalt steel has been lost in antiquity, but there you are. Perhaps the parts manual assemblers

were paid by the word...

When Class D (split) headphones were installed in a headband, the assembly was renamed as H-2/AR after the JAN

system came into being, using a 49510 headband. (The single cord headband is labeled 49503, which

evidently became the H-4/AR...see complexity mentioned above.) Note that the total of 600 ohms cited

above doesn't compute for those split, independent phones. I've tried using the one below simultaneously with two

separate radios and I have to say that it must be an acquired talent ... (Perhaps combat interphone

traffic would have been statistically less simultaneous than listening to two ham band discussions.) The photo

below also illustrates the Navy ear cushions mentioned above, the NAF 48490-1. Larger than the Army MX-41/AR, it was

an excellent platform to mount a boom mike, as shown on the H-46/UR below - something the smaller Army cushion would not support.

The Army evidently considered the chamois cushion a cleaning problem, but that didn't deter the Navy, which used them in hot climates to

great effect. USAAF operational folks evidently considered them prized acquisitions, according to anecdotal evidence, and when the H-46/UR

came out, the Army (perhaps reluctantly) began including them in their logistics chain.

H-2/AR headphones. The headband is engraved "CTE 49510", while the elements are marked "ANB-H-1A".

Exactly the same headband as above, but labeled as H-3/ARR-3 headphones on the cable - intended for the

sonobuoy system. The headband is engraved "C.Q.F 49510", while the elements are marked "Type 49456 (P/O H-3/ARR-3)".

There is no external difference compared to an H-4/AR, but the ARR-3 elements have an extended frequency

range of 100-6,800Hz.

Why split feed earphones? Unlike the AAC/AAF sets, the Navy came to grips with operational necessity way back

around 1936, when they produced the first multi-place interphone system, the RL-1. The split receiver headset

above is a reflection of that operational reality. The driver for this was a simple procedural problem - when an

aircraft was in a combat situation, internal interphone traffic was reserved for the aircraft gunners

and anyone watching for bandits. If external warnings from nearby aircraft were to be heard and prioritized, somone needed

to listen to them on a separate channel and convey them to the A/C and copilot for a decision. Because

of a single amplifier in the aircraft, typical B-17 and B-29 practice required decision makers to keep one earphone off

the ear to hear shouted warnings, an altogether unsatisfactory way of communicating

sometimes critical information. In contrast, for those multiplace aircraft that warranted the complexity, the

Navy installed an interphone system containing two independent amplifiers. During the war this was the

RL-24A, B, and C, a natural development of the original RL-1. Typically the radio

op, the pilot, copilot, and navigator wore an H-2/AR to be able to cover the two simultaneous

channels available. Before the end of the war, this perceived need for separate channels had become so acute that

another Navy interphone set was fielded that contained the ultimate in flexibility - five! different

amplifiers in one ATR enclosure - the AN/AIC-5. The

separate systems are labeled pilot, copilot, radio op, flight crew, and gun crew.

The evolution of the microphone and earphones into an integral, hands-free system occurred near the

end of the war, also led by the Navy. This headset, designated H-46/UR, left the hands free while being quite

comfortable in a pressurized cockpit or in supply aircraft that flew at low altitudes. It was vastly more

intelligible than the throat mikes used previously, and employed a

noise cancelling design that considerably lowered the volume of sounds emanating from sources

farther away from the microphone diaphragm. The carbon mike element (initially an M-6/UR, later versions marked

M-51/UR) was actually purloined by

its designers from a Marine Corps ground set lip microphone that looks extraordinarily uncomfortable

to use in its original setting. The USAAF quickly glommed onto this Navy originated headset, reflecting

the need to satisfy "real operator" requirements. See

Navy M-5A/UR for assembly instructions to the Navy canvas/leather H-4/UR headband units. By the way, I have run into a lot of M-6A/UR

elements which are cemented beyond repair by vibration or shock. The replacement M-51/UR element appears to be less prone to the cementing caused by moisture and time.

A couple of H-46/UR headset mike variations, showing simple riveted attachment method to

standard chamois earphone cushions.

Related to the plethora of component parts to these sets is the interesting array of plugs associated with

them. Below are some Navy and AAF variations of both the short "bail-out" and conventional phone plugs.

Various Navy and USAAF aircraft phone plugs. The high impedance HS-23 normally had a black PL-54 "bail-out" plug at its end, but I have seen

longer cords used with a PL-55 on the end to plug directly into a receiver or other audio source.

The bottom three are some of the aforementioned bail-out plug variations that began to be installed on headsets to reduce the danger of being hung up during combat operations.

It provided the transition between the short headset pigtail and an extension cord [CD-307 in Signal Corps jargon, C**-49534 (among others) in Navy speak, and JAN CX-4548/U], which

was then plugged into the interphone jack box or radio. The red PL-354 was used to identify a low impedance HS-33 during the

period when both HS-23 and HS-33 headsets were in use. The PJ-054R is exactly the same plug as the PL-354 but came later during a wave of trying to rationalize

connector designations to make the numbers more intuitively understood. In the process, the PL-54 and PL-55 became PJ-054B and PJ-055B respectively, the B of course

signifying black in color. Unfortunately, the end result seems to have been to introduce more confusion than clarity.

Almost as an aside, one has to wonder where the crewman hung his headphones when not

in use. The example below shows the 'elegant' way that Boeing solved the problem. For the ones in

the aafradio "flight deck", I put a generous radius on each side of the hole to prevent creases in

the leather headband that are evident in this Enola Gay example. I made a fabrication sketch for those who

might wish to replicate the hanger, and placed it here.

B-29 earphone hanger

Return to Aircraft Peripherals page